Write-atomata

Why me, Lord?

Here I am. Here in my little place in London, writing my way out of a special kind of madness.

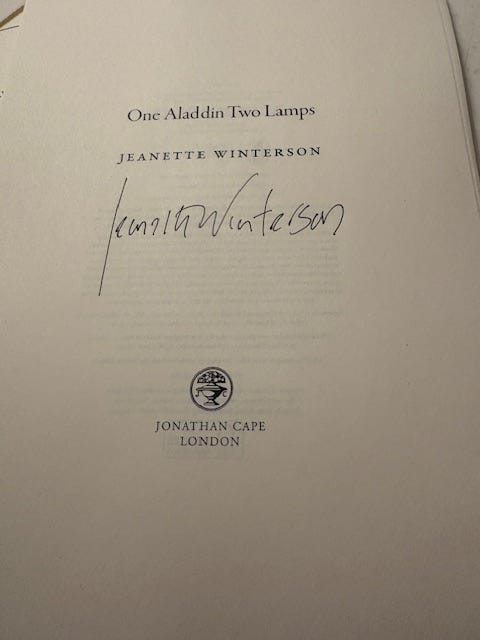

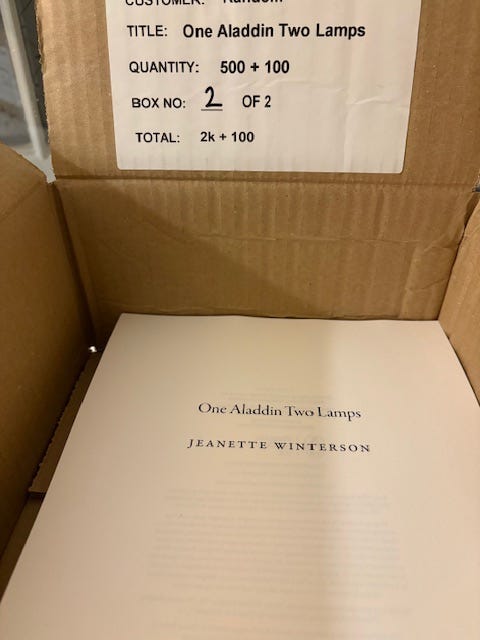

Yesterday, I arrived at my agents, PFD, on New Oxford St, and sat down to start signing tip-in sheets for my new book. These sheets will be bound into the finished copies. Yesterday, I had to sign 1000 of these things for my American publishers, Grove Press, who have published me forever. It took me 2.5 hours. I have 18 letters in my name.

When I had finished this horror, I walked through Covent Garden, down to the Strand, and along to an excelled restaurant I like, called Toklas. Named after Alice B Toklas, it starts from the belief that food should be be plentiful, natural, and without fads. They make their own wholemeal sourdough bread. The menu is small. We drank their house red, ate chops, pumpkin, home-made ravioli with fresh sage and salt-butter. Anchovies, beetroot… stuff that is good for you. Alice Toklas, lover of Gertrude Stein, spent her life running between the kitchen to cook Gertrude’s meals, and sitting at her desk to type up Gertrude’s prose. She didn’t mind… and after all, she got one of the most enjoyable autobiographies out of it… The Autobiography of Alice B Toklas (1933) all about their time in Paris from the early 1900s, till after the Second World War. It’s great fun… and she didn’t even have to write it. Gertrude did it for her. It is a piece of genre-defying greatness that makes up for all the word-spaghetti Gertrude wrote most of the time. The thing with prose is that it does have to make sense. We hope it will make a lot more than sense - that the language will get past utility. Our obsession with ‘content’ and ‘storytelling’ obscures this simple truth. With poetry, we don’t expect utility. With prose, we do. And that’s all right, if only there is more besides. Let’s not get lost in the literal.

Gertrude’s Stein war on the literal was rightly Modernist. What could be stripped away? What could be implied, not stated, how could the apparatus of social realism be subverted? How could prose bring about a shift in consciousness that depended more on the language and less on the story? What was the job of the novel anyway? Chunks of life laid out before us? Or something stranger? More beautiful and elusive. Stein thought she could do with language what her friend Picasso was doing with painting. No more ‘representation’. Who cares about likeness? How can a surface become a depth?

The problem is that language really does have to make a kind of sense. Language can’t be non-sense. Still, Gertrude really took a sledge-hammer to how to tell the story of your life. The Autobiography is, of course, the story of her life, but via a different voice. And it has the best ending. I love this ending. And remember, at the time, people were reading faithfully to the last page, thinking Alice had written it, and then…

“About six weeks ago Gertrude Stein said, it does not look to me as if you were ever going to write that autobiography. You know what I am going to do. I am going to write it for you. I am going to write it as simply as Defoe did the autobiography of Robinson Crusoe. And she has and this is it,”

FAB! Robinson Crusoe isn’t an autobiography - it’s a work of fiction pretending to be a true account. For all the folks who think that this clever kind of blending is something cool and new… well, Robinson Crusoe was published in 1719. When I was 24, and writing Oranges Are Not The Only Fruit (1985), I had in mind both Stein’s Autobiography, and Robinson Crusoe.

In this life, it helps to read yourself as a fiction as well as a fact.

And that’s the basis of my new book. One Aladdin Two Lamps.

It’s a reading of the 1001 Nights. It’s also a book about how to make a life. You can’t do that if you are lost in the literal. Life is more than utility. Life is lived best through the imagination. That’s where everything begins.

After my dinner, I walked back to my little place in Spitalfields. I walked down Fleet Street, up Fetter Lane, down Charterhouse St, past Smithfield, London’s meat market, still in use, but not for much longer. There had been a livestock market on the site for more than 800 years. This is an old city, a blood-soaked city. History is under your feet. It’s why I love to walk at night, especially though old London. I feel part of a bigger time, not just my own moment, but the past too. I can feel it, smell it. As I walked past, men in stained white coats were carrying pigs over their shoulders. Yes, I could put this on Insta, or Tik-Tok, lots of people do. Me, I would rather be there. Be there and store it in my mind. It’s riches that way.

Eventually, I wandered back to Spitalfields - once London’s fruit and veg market, and still operating when I bought my little house, a derelict dump boarded up for years. No water or electricity. A Dangerous Structure notice. A 1790s house. More history. More past. Sleeping here can be a challenge, as those of you who have read my ghost pieces on Substack will know. I wrote my ghost book, Night-Side of the River, (2023) because I feel I am often in a liminal place, the Dead close by.

This morning, after a few bumps and bangs from whatever spends the night here too, I went into my publishers, Penguin Random House, to start reading the audiobook of One Aladdin. I prefer to read standing up, to get the energy-flow. 7 hours later I was still standing up, still reading. Tomorrow, I must go back to finish the job. It’s a strange and wonderful thing, reading your own audiobook. I have done a few, and it’s an odd encounter with the self - like meeting yourself coming round a corner. As I read, this is me, obviously, but it’s also another me - the me who is made of words.

Coming back tonight, dumb as a saucepan, barely able to cut up an apple, I remembered I had to sign another 600 sheets. My heart sank - hearts do sink, it’s a cliche that is allowed - anyway, I hauled up my heart, did my washing, found my pyjamas, and got going. There’s 100 left for morning… but that’s with coffee. Next week, another 1500. Yes, it’s bonkers. The book becomes nothing but a frontispiece. A single line… someone’s name… a cryptic clue. I thought of a story where someone finds just the ripped out, or never sewn in, frontispiece. Would they try to find the book? Does it really exist? Do they find odd pages in charity shops? Do they write the in-between bits themselves?

Writing. A message in a bottle. A rope slung across time. What is found there.

What IS found there?

Let’s see…

.

Last year I went to London for the first time (my first time in Europe, actually!) As soon as I set foot there I felt a feeling I'd never felt before, deep human time underfoot, almost infinite. I'd never been anywhere so haunted. It was exhilarating but it also made me feel dizzy & almost sick, so I called it 'time-vertigo'. The locals were immune to it, I guess because they'd lived their whole lives on top of the layer cake of ancientness.

Goodness, that's a form of torture for a writer -- it's bad enough as a printmaker to have to sign print editions – there's a point at which you lose your sense of what your signature is and it starts to look alien. We could frame it as a mindfulness exercise but that doesn't help. Doing it in small batches helps, but what you're being made to do is ridiculous! All strength to your hand. I treasure all your books and none of them are signed.